Ever since Stacy Danielle Stephens sent us the amazing Bismark Excerpt from her historical novel, we’ve been looking for an excuse to run another long excerpt, and here it is. As always, a great look at the human elements in the world’s most important war in wold history – elements that are sometimes overlooked, just because WWII is too big a topic.

On 5 March 1943, Benito Mussolini fell from grace, although not yet from power, when workers at the Rasetti Factory in Turin went on strike. Bombing around the clock had come to the soft underbelly of Europe; the Americans were smashing the hell out of northwestern Italy, making a shambles of any factory they could put under a Norden bombsight.

Italians had been universally tired of the war for more than two years. Since the disaster in Greece, the only good war news any Italian had heard was that their son was a prisoner, and still alive, in a British or American camp. Now that war on the home front had descended from deprivation to destruction, Italian workers found themselves willing to oppose fascism and fascists.

When neither coercion nor violence quelled the strike, it spread; to other factories, and other cities. For the first time in eighteen years, Italy was not under Mussolini’s thumb.

* * *

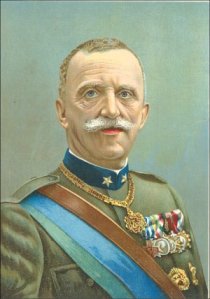

Throughout Italy in the spring of 1943, a consensus grew: Italy must withdraw from the war, and the Germans must withdraw from Italy. While it seemed improbable that the Germans would agree on either point, King Victor Emmanuel felt that Mussolini was the only man who might persuade Hitler to release Italy from the Pact of Steel; the only man who might extricate the country from looming disaster. That Mussolini had, more than anyone else, engineered and orchestrated each unfolding step of that disaster, seemed to escape the King. With the exception of Mussolini himself, this patently obvious fact had escaped no one else. As labour unrest escalated to political agitation, wealthy industrialists pressured high-ranking Fascist Party members to demand Mussolini’s resignation, and a handful of those Fascist leaders had begun soliciting support in order to arrange for his arrest.

* * *

On July 5th, 1943, General Vittorio Ambrosio, Chief of the Italian General Staff[1], met with King Victor Emmanuel, presenting a large number of lengthy reports, explaining that Italy could not continue the war. He further informed the King that the Allied invasion of Italy was imminent[2], and that Italy could not hope to repulse, resist, or survive that invasion. He concluded with the suggestion that the King immediately remove Mussolini from office, and appoint as his replacement either Marshal Pietro Badoglio or Marshal Enrico Caviglia. Still, the King took no action.

Meeting with the King later, Count Dino Grandi, a member of the Fascist Grand Council, advised him that if Mussolini were not removed from office soon, the King might be forced to abdicate. The King asked Grandi to give him constitutional grounds to dismiss Mussolini. A vote of no confidence from the Grand Council would be sufficient. This arrangement, which was precisely what Grandi had planned, would leave the Fascist Party in control of the Italian government.

* * *

For several months, Italy’s Foreign Minister, Count Galeazzo Ciano, had been aware that the governments of Hungary and Rumania were also seeking a way out of their alliance with Nazi Germany. Believing he could speak for those countries as well as Italy, Ciano asked Luigi Fummi, a Roman financier with connections in New York City and the Vatican, to travel to London under a Vatican passport for the purpose of opening negotiations with the British, to determine what they would offer, and what they would require in exchange.

At best, Ciano’s plan–if bluff and supposition can be called a plan–was inanely optimistic. When the allies began landing in Sicily, it was clear, even to Ciano, that it was now a matter of the King and the military negotiating an armistice, if anything short of unconditional surrender could be hoped for. Although the Fascist government was no longer in a position to bargain with anyone, Ciano fell in line with Grandi’s faction in the Grand Council.

* * *

On July 15th, Marshal Pietro Badoglio met with King Victor Emmanuel, proposing that several non-Fascists be appointed to a coalition cabinet. The King was still undecided about what he should do or when he should do it.

* * *

On July 17th, SS Captain Eugen Dollmann, who had both worked as a journalist and served as a diplomat in Rome, notified the German Government that Mussolini was seeking release from Italy’s treaty obligations, and a means of ending hostilities with the western allies, at the urging of the King, the army, and the Fascist party.

* * *

At Feltre, Hilter began–and concluded–the “discussion” with a two-hour lecture, pausing only a moment at eleven-thirty, when a messenger entered to inform Mussolini that the Americans had bombed Rome in a massive raid. At one o’clock, Mussolini stood and said, “We fight in a common cause, Fuehrer,” thus letting Hitler know their meeting was at an end.

“Our secret weapons will be ready by winter,” Hitler added before Mussolini could leave. “Italy must hold on until then.”

While Hitler and Mussolini were conferring, General Ambrosio spoke with German Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel, who explained, rather impolitically, that Germany intended to secure Northern Italy, from Rome to the Po valley, expecting the Italian army to delay the anticipated British and American advance up the southern half of the peninsula. Ambrosio argued that German mechanized units would be more effective against the western allies; the poorly-equipped Italians should be moved north, where they could be reinforced with fresh recruits and strengthened with new materiel. Keitel would not discuss the matter further, not wanting to spell out what Ambrosio had already discerned: the Germans were fully aware that Mussolini might be deposed at any moment, and didn’t doubt that his successor would attempt to negotiate an armistice with the west; with the exception of Smiling Al Kesselring, no German officer wanted to face an advancing Allied force with any Italian units covering, or perhaps preventing, their retreat.

[1] February 1943 to November 1943

[2] Ambrosio’s insight was not so prescient as it may seem. For the first several days of July, 1943, Sicily had been bombarded with propaganda leaflets blaming Mussolini and the Germans for what was about to happen.

5 comments